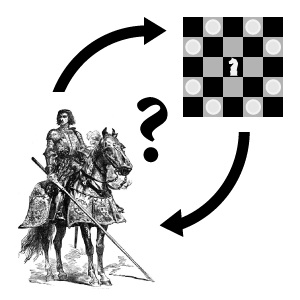

Which came first, the theme or the mechanics? Knight image from Giant Bomb.

One of the fundamental questions in game design is: which came first, the theme or the mechanics? Different designers have different answers to this question, some holding their answers as sacred as scripture.

While I don’t have strong feelings on this question (I have been inspired by both themes and mechanics), I tend to lean towards mechanics. Even when inspired by a theme, I strive to convey the theme through novel, interesting mechanics.

Today, I want to talk a little about theme. Specifically, I want to talk about what makes a game feel thematic. I feel like there is a disconnect between what many people think makes a game thematic and what actually makes a game feel thematic when you play it. My hope is that designers who read this will avoid common traps when trying to capture a theme in their games.

Thematic Games

What makes a game thematic? Unfortunately, in the board game community, the word thematic is often associated with a term I have grown to loath: Ameritrash. This derogatory term refers to bloated games with more appearance than substance. Even though their rule books are huge and they have tons of components, these games often come down to chance.

Why are Ameritrash games considered thematic? For one thing, the games often rely on theme–there isn’t enough game behind them to sell (or even be played) without a heavy injection of intellectual property. For another thing, these games often involve unfathomable amounts of art, plastering the theme all over the game. Finally, these games often incorporate everything related to a theme. Their component count is huge, and that’s because they must contain the entirety of their theme. Anything related to the theme not in the base game is undoubtedly being saved for the expansion.

It is unfortunate that thematic games are often conflated with Ameritrash games. (To be fair, the Ameritrash games described above are the most extreme, and there is a sliding scale of games in the family.) To me, a more thematic game isn’t one that captures every possible trope from a theme; it’s one that makes you feel like you are experiencing the theme first hand. And you’d be surprised how little is actually required to make a player feel like that.

Thematic Games: What You Need

In my last post, I discussed how to keep the scope of your game down. One of my main recommendations was to find the core of your game before adding frills, and then build out from there as necessary. The same advice is very useful when it comes to making your game feel thematic: find the core of your theme, and make that the core of your game.

The core of your theme should be specific feelings the player should feel or certain actions the player should take. In a horror game, you want your players to feel anxious. In a game about emergency personnel, you want your players to feel panic and urgency. In a game about courtly intrigue, you want your players to value information and for plans to conflict with each other in unexpected ways.

Whatever the core of your theme is, identify it and strive to achieve it with as little as you can. After you’ve mastered the core, then you can start adding additional components and special rules to flesh out the theme a bit more. But remember: your game could be plenty thematic even with just the core.

Thematic Games: What You Don’t Need

Like many things related to game design, what you don’t need for a thematic game is more revealing than what you do need. Here, I want to point out some features many people consider thematic, which are generally not necessary to make a game feel thematic.

Everything. When you’re first working on a new thematic game, it’s often valuable to brainstorm concepts related to the central theme. The next step, which many people ignore, is crucial: throw most of it out. Brainstorming is intended to discover the most important concepts, not to be a minimum feature set. By including everything you can think of, you’re filling your game with suboptimal content that forces your player to learn many more rules, increases the game’s price, and takes away from the central focus.

Ticket to Ride is about laying tracks, even if it doesn’t have any hobos. Image from Board Game Geek.

You’d be surprised with how little is needed to convey a theme. Take Ticket to Ride. The game may not be winning any theme awards, but no one will question its theme, despite the fact that it omits many important features of railroad building, such as resource acquisition and transportation, legal wrangling, station building, even cargo and passengers. The game makes you feel like you’re laying tracks, even if the specifics are missing.

Everything about something. Let’s assume you’ve decided that you absolutely need to include something (a character, an item, etc) in your game. Is the next step to accurately model every detail about that thing? Definitely not.

You’d be surprised with how few special rules you need to convey a concept to players. Often times, one simple special rule will give the player a clear image of a character or an item. Take the roles in Pandemic. Even though each role has only a tiny rule tweak, those special rules clearly convey what’s unique about those characters.

Thematic justification for all rules. While you will want your core rules to be thematically justified (and really thematically driven), you’d be surprised with what you can get away with in terms of rules that make little thematic sense. It comes down to most players looking for theme, rather than looking for where the theme breaks down. Assuming your core is solid, the rules you need to make the game work will usually be overlooked without much question.

Molecules in Compounded grant arbitrary skills, and no one minds. Image from Board Game Geek.

Take Compounded, the recent chemistry themed Kickstarter success. The game embraces its theme in every way. Even so, there are plenty of rules that have no thematic justification, but no one seems to mind. For example, why does calcium oxide upgrade your study ability? I welcome any chemists to correct me in the comments, but I think the answer is that the game needed a way for players to get upgrades, and they were already working towards making molecules. Why not add an extra reward? In other words, there’s no thematic justification for it; molecules offer different upgrades because the game needs them to. And you know what? Compounded still feels very thematic.

Thematic Inspiration

Is your new game idea inspired by a theme? Awesome! My hope is that you’ll resist the urge (and all too common practice) of feeling like you need to jam as much about that theme into your game as you can. It’s very possible to make a thematic game that is elegant and concise.

Yabdar

/ January 11, 2014Yea I agree with you in terms of the theme inconsistency with compounded. It’s definitely a fun game, but it doesn’t make much sense if you think about the upgrades you get when you complete the molecules. I feel like a publishing mechanic, similar to the game The New Science (http://boardgamegeek.com/boardgame/114667/the-new-science) might make more sense thematically to upgrade abilities like research, study, etc. For example, you can go through the normal process of discovering the molecules, but then if you want to upgrade other abilities you can then try to publish your findings and then receive the appropriate upgrade(s) if you are successful. Although a problem with this could be that the game could be running longer than normal, and you will be introducing even more rules to the game.

Dave Lerner

/ February 15, 2014I virtually always start w/ theme, then try to develop a mechanic that fits.