People play games for lots of reasons. One particularly dangerous reason is schadenfreude.

The concept of schadenfreude was popularized by a bunch of puppets. Image from ThirdCoastDaily.com.

Schadenfreude is a positive emotion (something like happiness or fun) that people get from the negative emotions other people feel. Those negative feelings don’t have to be caused by the person experiencing schadenfreude, but it certainly doesn’t hurt. Today, I’ll mostly be discussing schadenfreude caused by one player picking on another player.

Games offer players a relatively safe space for people to experience schadenfreude. If you feel joy from other people’s real life misery, you might be called a “dick” (or worse!). In a game… well, you still might be called names, but at least you’re only feeling joy from someone’s artificial pain, right?

I actually believe schadenfreude is quite dangerous, even in the relatively safe space of a game. Today I want to discuss why I think it’s something that should be carefully controlled, if not avoided all together, and some strategies for containing it.

Beware the Schadenfreude

I’m just going to come out and say it: when I play games, I become pretty evil. Well, maybe not evil, but certainly merciless. I really enjoy taking on the role of the super villain.

I’d be lying if I said that I haven’t driven multiple people away from games with the way I relentlessly attack them. To me, I’m just playing a game the way it’s supposed to be played. But to them, I’m completely ignoring their feelings.

(In real life, I’m actually a pretty nice guy. Honest.)

It might just be a game, but the emotions are real. Image from a tumblr full of table flips.

“It’s just a game” is a phrase that gets thrown around way too often. As games become more prevalent in our lives and take a bigger chunk of our leisure time, it’s important to recognize that while a game might be a self contained, fictional universe, the emotions we feel and the ideas we get from playing games are very real and continue to affect us even after the game ends.

Of the many reasons people play games, feeling dumb or bullied don’t usually make the list. You might think that you and your friends don’t mind getting picked on, but you and your friends have probably been playing competitive games for a long time and are used to losing now and then. For less serious gamers (who make up an ever growing percentage of gamers), other people laughing at them could be enough to make them never want to play your game again.

Managing the Beast

Do you need to dumb down your game so the most emotionally fragile players won’t get their feelings hurt while playing? Definitely not. Including some possibility for schadenfreude in a game is fine, but it’s important to be mindful of how much potential for griefing there is in your game. By considering the opportunities for schadenfreude while you design your game, you can create an experience that doesn’t feel dumbed down at all but still minimizes the chances your players will feel both insult and injury. Below I’ll cover some strategies that can help you with that.

Avoid zero-sum games. In a zero-sum game, whenever one player does well, he or she does so at the expense of the other player(s). Famous zero-sum games include Tug of War and Checkers. Hurting the other players is built into these games: by definition, advancing towards victory means dragging down your opponents.

Two player games in particular have a hard time avoiding the zero-sum quality, but there are ways to combat it. In fact, many eurogames, such as Puerto Rico and Race for the Galaxy, do a good job of this. Rather than destroying what other players are trying to create, players in these games race to create the best engines they can as quickly as possible. All players are building up, but the winner is determined by who can build up the best.

Games with trading also involve player actions that benefit multiple parties. In Settlers of Catan, it is quite common for both sides of a trade to walk away happy with the results.

Protect emotional investments. Many games involve working towards big, exciting things, be they constructing magnificent buildings, harnessing the power of giant monsters, or creating zany machines. Your players will work hard to achieve these goals and will therefore invest a lot of emotion into them. Don’t let other players erase all that work with one fell swoop!

Often times, you’ll need to include some way for one player to hamper another. If you include something like this in your game, there are a few options less painful than destroying something with a lot of emotional baggage. For example, delaying the exciting thing by a turn or two will usually end up having the same effect as destroying it, but it feels much less bad. Alternatively, instead of completely destroying the big, exciting thing, allow the other player to weaken it.

Or put the defense in the hands of the player protecting his or her baby. This can be done by allowing the player to take out insurance to protect it (having to wait a little longer or pay a little extra to give the exciting thing extra defense). Or give the defending player the choice of what dies when attacked. This strategy is commonly used when players have to discard, but it can easily be used for other types of attacks as well.

No alarms and no surprises. One reason losing something big and exciting can be so devastating is that it comes out of nowhere. You think what you’re doing is safe, and suddenly it’s gone. You can combat these negative shocked feelings by not letting players come out of nowhere and upset another player’s plans. Give the player a warning and a chance to react in a meaningful way. This may weaken attacks, but strong players can use these actions to distract weaker players from what really matters in the game.

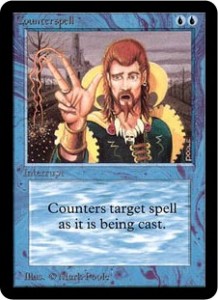

Just look how sad counters make players. Image from the gatherer.

In my experience, counters are the worst offenders here. They come as surprises out of a player’s hand, attack something exciting before it has a chance to defend itself, and offer a very small window for reacting against them. Not to mention they greatly complicate timing. Whenever I can, I avoid including counters in my games.

Control freaks. Nothing is worse than when one player achieves total control over the game. After taking a lead, that player prevents the other players from ever doing anything, let alone making a comeback. The controlling player is often having the time of his or her life, but the other players’ helpless feeling is never fun.

There are two ways of combating this problem. First, make sure there are comeback mechanisms in your game (there should be anyway). And make sure your comeback mechanisms genuinely help the players who are behind and can’t be exploited by the leading player.

Second, avoid resource denial strategies. Often times, a player takes control of a game by monopolizing one type of resource or by otherwise starving the other players from something necessary to take meaningful actions. If your game has ways of denying resources, make sure those strategies are limited, so other players become hobbled and not completely crippled.

Good Clean Fun

There are many ways people enjoy games, and schadenfreude just happens to be the most dangerous of them. When I experienced schadenfreude, I often wasn’t even aware of it–I was simply losing myself in the game and didn’t realize I was hurting my friends. As a game designer, it’s your job to make sure everyone’s having a good time, and when one player’s joy is at the expense of another player, you should step in to stop it.

Ultimately, how much opportunity you include for schadenfreude should depend on your player base. Some people just eat that up. But remember that every possibility you add for players to be nasty to each other will alienate potential players. Including some in your game is probably a good thing, but make sure you’re aware of how much is in there.

Adam Wardell

/ July 9, 2013Good article Teale! I remember reading an article on the MTG website some time ago talking about “griefing” and what the designers for MTG do to combat it. They don’t want to eliminate shadenfreude; there are some players, such as myself and apparently you ;] who really thrive on that emotion in games. So they intentionally make some cards with griefers in mind, but they make them either prohibitively expensive or deceptively ineffectual. Examples are Cancel, which unlike its younger brother Counterspell is too expensive to effectively lock out an opponent with, and Tome Scour, which griefs the opponent by “getting rid of” potential good draws, but doesn’t actually affect the state of the game (on its own, at least). With those cards, a shaudenfreude-happy player can grief an opponent without actually ruining the game for them. Of course, a lot of bad shaudenfreude has made it past R&D into that game too, so they’re far from perfect. But they’ve been improving.